Pubs, pies and prawn cocktail crisps are just a few things that Dylan Earl loves about the UK and keeps him coming back. Therefore, an old Victorian pub with dark wood furnishings, low tables, dimly lit with an open fire, which made Dylan’s eyes widen with delight, and a stone’s throw away from Denmark Street, was the perfect place to meet after his album launch at Rough Trade. “I love these little old geezer pubs like this because the whole thing is about a good conversation,” declares Dylan. “I think that third spaces like this, low tables are really important to levelling people. No one can be the big guy at a low table.”

A couple of drinks in and after his fourth pie of the tour so far (this was day four or five), no stone was left unturned: From the beauty of Arkansas, his songwriting process and weirdos in the holler, to the social and political climate in the States and working-class solidarity, to lessons learned touring in the UK, by way of craving each other’s crisps flavours, Quanah Parker, Steve Martin in The Jerk, and of course his new album, Level-Headed Even Smile. Not only is Dylan Earl a fantastic singer and songwriter, with a voice as smooth as honey and the best moustache in country music, he’s also wonderful company and conversationalist: charming, honest and not afraid to speak his mind. “We came here to sit down and get cosy and have a really important conversation.”

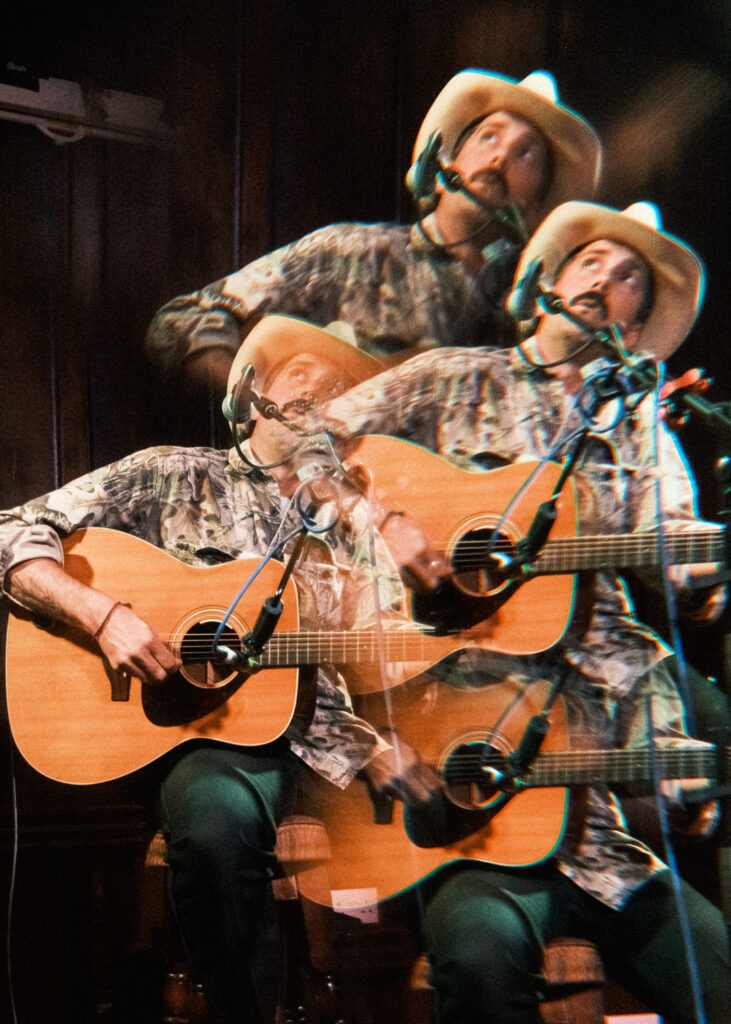

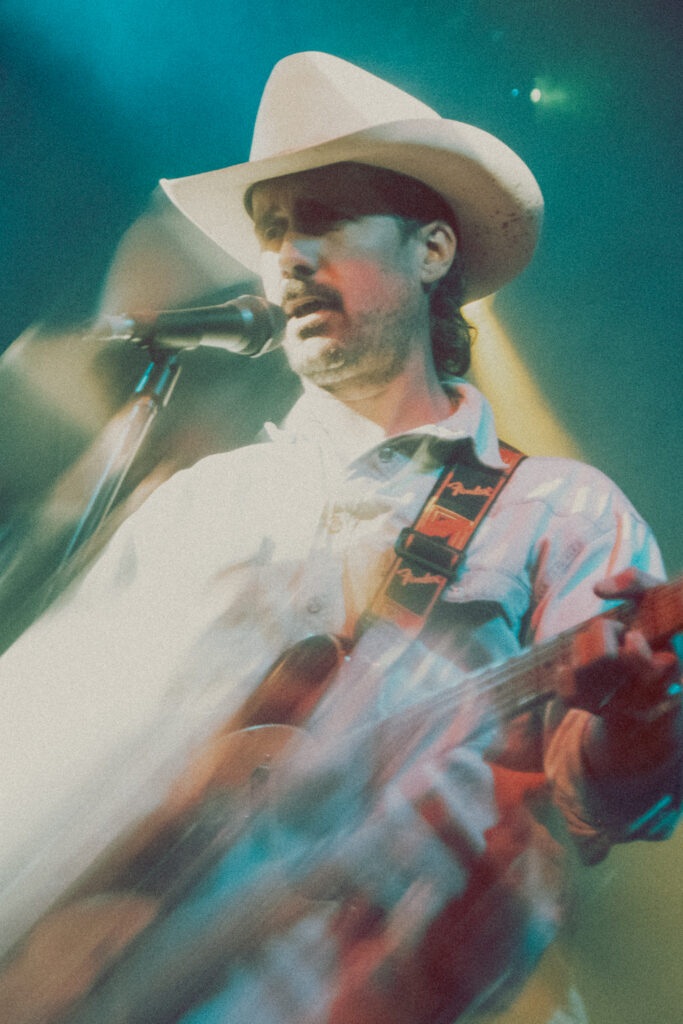

2025 has been a busy year for Dylan Earl, with a packed touring schedule that has seen him play in almost every dive, honky-tonk, record shop and pub on both sides of the Atlantic, as well as the release of his fourth studio album in September, Level-Headed Even Smile. “It’s probably my favourite collection of songs to date,” Dylan says on the album, which could perhaps be best described with the same words that his label, Gar Hole Records, use to describe the man himself: “loveable, alt-country hippie.” With his crooning voice singing songs about his friends, surroundings and youth, the album has a beautiful sense of togetherness and warmth.

In some ways, Level-Headed Even Smile is a love letter to Arkansas, a state he’s called home since moving there from Louisiana after the hurricanes in 2005, a time in his life he wanted to capture in the album. ‘Little Rock Bottom,’ ‘Two Kinds of Loner,’ ‘High On Ouachita’ all focus on his navigation through good times, bad times, youth, friendships and nature in the Natural State, as well as a cover of Jimmy Driftwood’s ‘White River Valley,’ an Arkansas folk singer, environmentalist and inspiration of Dylan’s.

He was also keen to avoid classic country music tropes, like whiskey and ‘she left me’ songs. “I feel like that’s such a cliché trope in country music, especially as you’ve seen a whole lot more young up and comers that are joining the whole country music marketplace and are just singing a bunch of ‘she left me’ tunes,” he notes. “Which ain’t nothing wrong with that, and I’m definitely gonna put out a record in the near future that’s just gonna straight up be ‘she left me’ tunes, but I really wanted to do something that didn’t have anything that was centred around a ‘she left me’ moment.”

Alongside Dylan’s Arkansas, nature, friendship and navigating youth songs, there are free and single songs with ‘Lawn Chair,’ a cover of the beautiful ‘Rock Me To Sleep,’ a Utah Phillips song, who was a poet, folk singer, social activist and close to Dylan’s heart, and songs of our whacky timely issues with ‘Outlaw Country’ and the titular track. “It’s just gotten as whacky and awful every time I turn my fucking phone on, it’s terrible, and I just try to keep a level-headed even smile in spite of it all.”

Now, you might be thinking, “wait, what about ‘Get In The Truck?’… Though he says he doesn’t have a particular songwriting process, it’s usually when he’s driving in his truck, “in silence like a total psychopath,” that melodies or lyrics will pop into his head, and he’s sometimes singing the same hook for six hours. Other times he’ll sit and write for hours or give melodies to old poems he’s written. “I wish that I had a better strategy for it because I’d be able to predict more when it was gonna happen,” he says on his lack of a process. “That’s the problem, that it’s completely unpredictable, and you just kind of sit there sometimes and be like, ‘well I sure as shit hope a fucking song comes along one of these days because I’m getting tired of these,’ you know? So, I’m really really eager to write some new tunes.”

I did argue, however, that if his writing process was too predictable, he might lose some of his spark. “I mean that might be it, you know?” he agrees. “It’s fun to just kinda get hit in the gut with an idea and to move through that and to become the moment sometimes.” Especially where he likes to capture memories through song. “If I can somehow capture that feeling and focus on it and harness it, then I can write words around that, and that’ll place that song into that feeling and emotions.” As well as write from a sensory perspective: “If I ever feel that a smell, metaphorically smell something from the past, I try to just sit there and sniff it, sniff it, sniff it, until it’s just I’m there and I’m completely immersed and you write your song from that angle.”

Outlaw became a bit of a buzzword in the country world this year. Discussions were had online on who and what is outlaw now, as well as passive aggressive social media posts about it between singers, proved that the meaning of the original movement has become a little lost and maybe even forgotten. So how does Dylan Earl define outlaw country? “Outlaw country is no fascist, homophobe, racist bullshit.”

Dylan is undoubtedly inspired by the original outlaws and is arguably one of the few true ones in today’s music. Signed to an independent label, he has creative freedom and is vocal about issues, Dylan is what the movement was originally all about. Although he might be hesitant to define himself as one, as he does not like it when singers proclaim themselves as outlaws in song. “It’s like punks, it’s the least fucking punk thing to do is talk about being punk. You don’t talk about fucking fight club dude,” he laughs. “If you’re sitting there talking about being an outlaw, you’re not a fucking outlaw.”

“They were just completely anti-capitalist, anti-nationalist and they were anti-fascist,” he says with passion on the repackaging and commodification of outlaw country. “And then it’s just been so frustrating to see that term be commandeered and packaged in a way that’s misrepresentative of its origins.” And it’s this misrepresentation of not just outlaw country, but also of people’s perception of him, a mullet-wielding, camo-wearing country singer from the Deep South, that led him to write ‘Outlaw Country.’

“I was kind of inspired by Johnny Cash’s song ‘Man In Black,’ because it’s a straight up, ‘okay y’all, like love my old country stuff, that’s great, and glad y’all out here to honky-tonk, but I don’t take no racist bullshit.” Similar to ‘Man In Black,’ ‘Outlaw Country’ is an anthemic description of who Dylan Earl is, what he and his music stands for, and as a message to those who have misnomer him “to make sure that those fuckers knew I see ‘em.”

More importantly, he wants the song to be more than just about him. He wants it to be a tool for uncomfortable conversations in such divisive times, a call for working-class solidarity, as well as a reminder that “those people at the top aren’t left or right.” He also wants to let people know who are not from, and/or have never been to the South, that neither country music nor Southerners fit into one stereotypical box. Deep in the holler near where he lives, you’ll find weirdos, queer people, trans people, hillbillies and rednecks living with neighbourly love and community.

“Some of the most beautiful shit I’ve ever seen is holler solidarity and it’s important I think to represent a little bit of that, because I know there’s no reason for anyone here in London to fucking know that even exists,” he says with a huge smile. “It’s exciting for me to be like, ‘dude, come on out there and see this type of people that exist, it’ll make you cry,’ because it’s the most wholesome, beautiful fucking thing in the world out there is some of these places. Man, I just, I love it.”

Dylan Earl is man of the people. Not only is he excited that his music is played on satellite radio in the States, but especially when it’s played on the small, free, local stations. “The free radio is what’s really important to me, the public radio, that means that the word’s getting out to people who aren’t wealthy, and that’s the most important thing.” If you’ve ever been to one of Dylan’s gigs, you’ll know he loves interacting with his audience during, in-between and after his sets. He’s had tequila shots with my friend Geraldo in Austin, I’ve been serenaded with some karaoke-style Merle Haggard, and he always takes time to stop and talk to anyone. You can tell he enjoys these interactions as he has a knack for remembering names, faces and conversations. And for us fans, it breaks down the fourth wall, so that you feel like you’re seeing an old friend.

Audience-wise, you’ll see OG country fans, folk heads, Trendy Wendys, punks and a lot in-between. You’ll also start seeing the same faces, some you can tell he’s known for a long time, which is unsurprising since he’s been playing here for the past 13 years. “No one gave a fuck about country music here,” he says on the first time he played here at an open mic night for songwriters with a plastic guitar he had bought from an old Spanish man in Tower Hamlets who had recently been dumped (a country song in itself), a denim suit and cowboy hat. “People were like, ‘what is this dude’s deal?’ and I was just so freaked out in there,” but he would win the crowd of twenty-five over. “The way people were quiet and considerate, and gave a damn about my songs, I just couldn’t believe it, and that’s what I came to find.”

Learning how to understand and play to an English audience is a skill he is proud to have learned and appreciates our silence. “I thought about tonight, I was like, man, if I was fresh into this, I could imagine like a TikTok kid, I would’ve been sweating that I suck,” he says on the Rough Trade gig, full of quiet mouths and eager ears. “But I was like, ‘oh I’ve got ‘em.’ I knew I had y’all because I’ve done it before, and it’s like a skill you get taught just from experience playing here and I’m grateful for it, I’m really really grateful for it and I’m gonna take it with me.”

His touring on this side of the pond is now done for the year, but he still has some December dates in Nashville and North Carolina if you’re in the area. If you unfortunately missed out on seeing him, he didn’t say when he’d next be back, but considering he came over twice in 2025, the prawn cocktail crisps will undoubtedly be calling him back in no time. Besides, he has a dream he wants to achieve: to be on Whispering Bob Harris’ show. “So, Bob, if you’re listening, I wanna be on your fucking show dude!” Let’s make it happen 2026.

Level-Headed Even Smile is out now, and in this Christmas season please consider giving this album in its physical form as a gift to yourself or a friend.