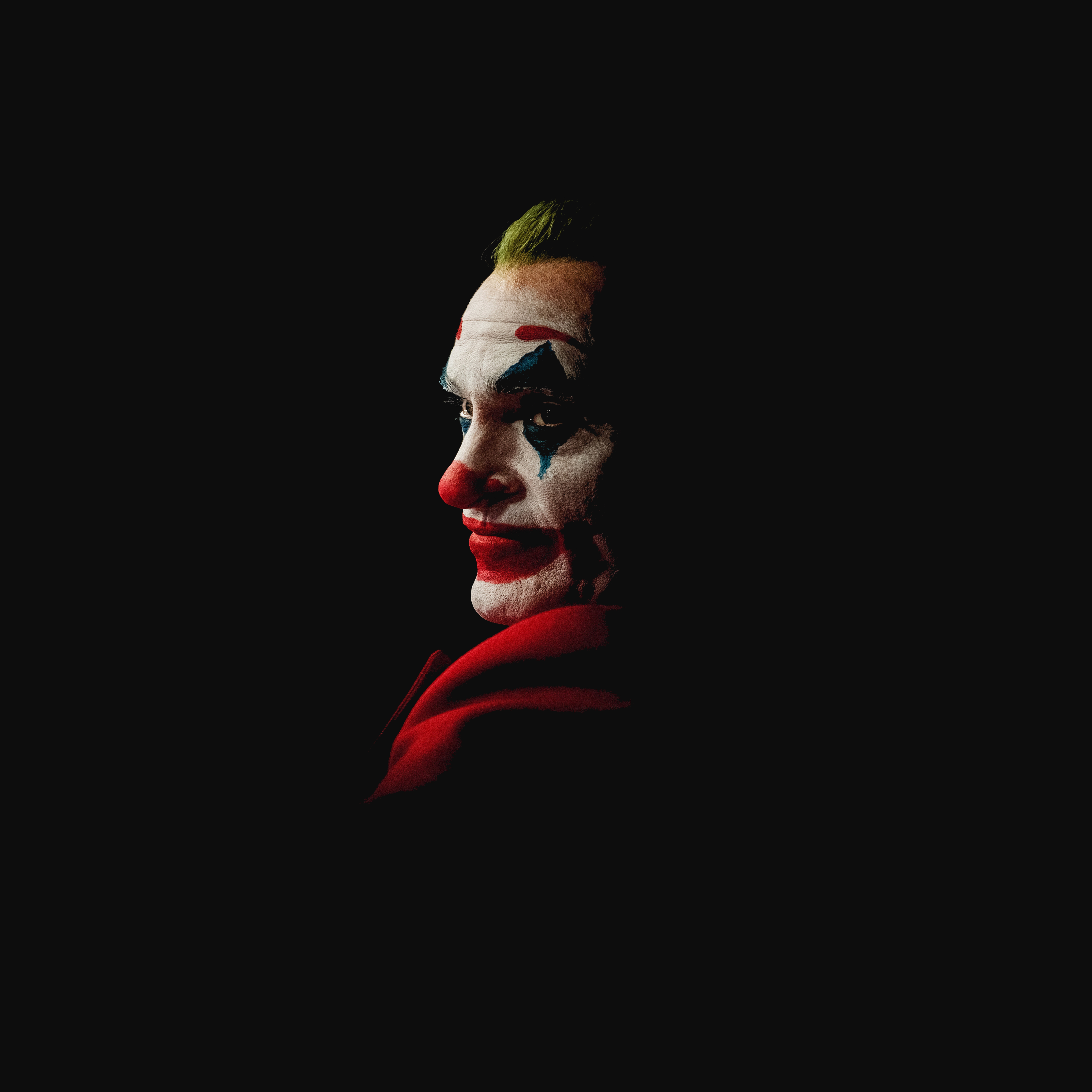

Joker is a film about personal, social and political darkness. Its main protagonist turned anarchist is a body and soul riddled with grief, anger and confusion, running from one disaster to the next as a twisted and taut human being. His mental state, his financial state, and his moral state are a dark and bleak comment on us, you and me, and the society we build: “All of you,” he spits during the film’s climax: “the system that knows so much, you decide what’s right or wrong. The same way that you decide what’s funny or not.”

It’s a violent but blunt film. Where it comes from, who it’s inspired by and what it wants to say are anything but subtle. 70s-style reflective cinema, Scorcese, and anarchy. Many critics, even memers, have pointed out these things, gone into detail with them, and achieved next to nothing but superficial nods of the “I know more than you” kind. References are being pulled from thin air.

But, there is one character, one story, that people have yet to point to. At a pivotal moment in the film, Arthur Fleck packs up his belongings after he’s been fired as a children’s clown. The scene represents Fleck’s symbolic unmasking of his newfound identity, Joker, the humour he’s strived to get before through poorly written jokes he finally achieves through violence, literally “punching out” his time card and box off the wall.

Whilst this transformative scene plays out, Jackson C. Frank’s ‘My Name Is Carnival’ can be heard. The song just so happens to refer to Arthur’s stage name, ‘Carnival’. As with the rest of the film’s overt references, this isn’t mere coincidence.

Arthur’s story is a comedy he proclaims, but tragedy is really his motive. Tragedy is the films entire motive. It seeps into every interaction, every win and every loss Arthus has. From the timing of his laugh in a crowd to the retrieval of his mother’s hospital records, every event and expression seems to be marred by negativity or a negative reaction. He, as I said before, can’t outrun his own bad luck.

Tragedy is the link here. The life of Jackon C. Frank, the man who soundtracks Arthur Fleck’s symbolic unmasking, was most definitely a tragedy. He too went from one life disaster to another, straining to bear the weight of humanity in all its harshness. His mental health too suffered as a result, and society too left him high and dry. He was a folk singer cast aside, uncared for and underappreciated in his art. His story is his tragedy. A tragedy not too dissimilar to what created the villain Joker.

Jackson C. Frank was just a regular Joe with an irregular story. He was born in 1943 in Buffalo, New York. He had split parents, his father an Army officer, his mother a remarried housewife. He was one of the first of the baby boomer generations, a blank slate and a new start for America and the world.

Civilization was starting to come out of the shadows back then; the war was won in the West and the East would soon follow suit. Optimism was growing as people’s husbands, brothers and fathers were nearly home. Jackson had, at his feet, a future, and a good one at that, one without fascism and hatred. But, his life would be nothing but suffering.

At 11, he attended Cleveland Hill Elementary School, New York, where he had a childhood sweetheart, Marlene Du Pont. One day, a day like any other in the classroom, the school’s heating furnace exploded under extreme pressure killing 15 of Jackon’s classmates, including Marlene. This event would scar him both physically and mentally for the rest of his life. Tragedy.

“And though the fire had burned her life out / It left me little more / I am a crippled singer / And it evens up the score,”

During his rehabilitation, his then teacher bought him a guitar and he became obsessed, like so many other 50s kids, with Elvis, the pivoting king. When he was 13, two years after the accident, he would meet his idol in Graceland.

At 21, Jackon’s life would change. He received a $100,000 as an insurance payout. Now, a budding folk talent, he left America guitar-in-hand, hoping to leave his past on that charred desk.

For a time his pain subsided, and in ’65 he met Paul Simon and recorded his eponymous debut. Life was looking up. Jackson became engrained in a burgeoning British folk scene, one that had already spat out Bob Dylan two years prior.

But, the pressure proved burdensome and his anxiety had not subsided. His writing reflected on the disaster that occurred during his childhood; ‘Marlene’ saw Jackson go over and over the loss of his childhood sweetheart. Every night, when people prodded him for songs he had to return to those memories, and it took its toll. It turned out that Jackson could not outrun his past. Whilst recording his debut, he insisted that Paul stood behind a shield: “I can’t play when you’re looking at me,” he would say repeatedly. Wherever he went, wherever he’d go, his past was never too far behind him.

“I want to be alone / I need to touch each stone / Face the grave that I have grown / I want to be alone,”

In 1966, his mental health and life began to unravel. Freind Al Stewart recalls: “[Frank] proceeded to fall apart before our very eyes. His style that everyone loved was melancholy, very tuneful things. He started doing things that were completely impenetrable.” Just a few years later his son died of cystic fibrosis and he was committed to an institution.

Ten years later, when the light at the end of the tunnel was near, he ran out of insurance money and began begging. Ten years after that he was homeless and destitute in New York City, declared a schizophrenic by doctors.

In the space of 30 years, Frank would go from one set back to another never capable of regaining stability and safety. He would die of pneumonia and cardiac arrest in 1999, blind in his left eye after a kid shot him in the street with a pellet gun.

Frank’s one and only record is his lasting self. The self that tragedy couldn’t touch. It is a triumph, humanity in its most painful relenting state, and humanity in all its glory. Sorrow meets serenity, his memories both good and bad clashing.

It is a cliche to say that an artist has to suffer to create something that lasts forever, but Jackson suffered and suffered, and created one of the purest albums ever written. Complete honesty. Though a harrowingly sad story, it is his silver lining.

The same can’t be said for Joker. Arthur turns pain into violence, Jackson turned his pain into honesty and humanity. Arthur kills people, Jackson, of course, did not. But the link between the two stories, one fact, one fiction, can nonetheless be made.

Tragedy is the pivot of both their characters and tragedy decided what direction they each took. Both moved from one world-shattering moment to the next. Both became tortured souls. “My Name Is Carnival” is more than a soundtrack filler. It’s a reference.

Listen to Jackson C. Frank on Spotify and Apple Music. Get the latest copy of our print magazine HERE.