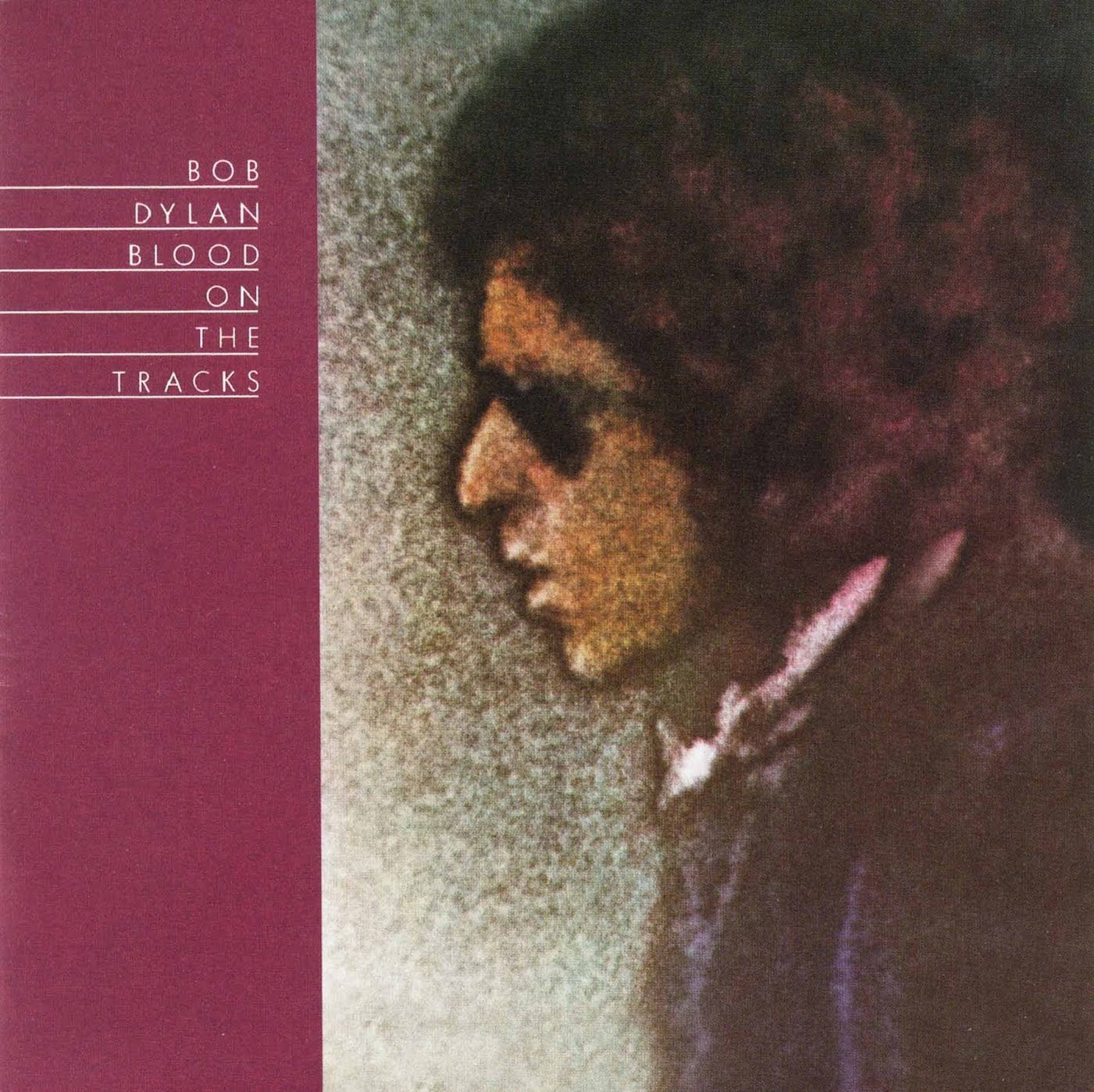

To celebrate National Album Day, we’re going through the albums that mean something to us and telling the stories behind what makes them so special.

Recorded in the fall of 1974, Blood on The Tracks saw Dylan return to his roots from the perspective of an older, more beat-up version of himself. Back in New York City, the place where it all started, Dylan turned his back on his country persona in search of becoming again an honest bard.

With an acoustic guitar in hand, he penned and penned letters of love and loss, scrawling down every word in anger and blood. The result was a record that defied expectation and explanation. Nothing before or since has had the kind of brutal honesty and grit you’ll find here in the grooves.

The lines are abstract storytelling and scene-setting, dealing one finishing blow after another. They play with narrative and time, appearing to jump from one moment to the next in the same way thoughts might. Dylan had spent time with painter Norman Raeben who supposedly had opened up his writing style to creates this; “[Raeben] taught me how to see … in a way that allowed me to do consciously what I unconsciously felt …”

It was gravity which pulled us down,

And destiny which broke us apart,

You tamed the lion in my cage,

But it just wasn’t enough to change my heart,

Now everything’s a little upside down,

As a matter of fact the wheels have stopped,

What’s good is bad, what’s bad is good,

You’ll find out when you reach the top,

You’re on the bottom,

The tension and strife of the record reflected his estrangement from then-wife Sarah, one figure amongst many, who listeners have recognised in Dylan’s more bitter lines. “You’re an idiot babe / It’s a wonder that you still know how to breathe.” In many ways it’s Dylan’s Cohen record, obsessing over intricate detail and women, his own misgivings and regrets laid bare. It moves and flows from one track to the other, each in the same key, the same tuning and the same tone. This “flow” moves like a stream of consciousness from one falling moment to the next, giving us an incredibly personal set of stories.

Sometimes he will have several bars, and in the next version, he will change his mind about how many bars there should be in between a verse. Or eliminate a verse. Or add a chorus when you don’t expect.

Phil Ramone, Session Engineer for Blood On The Tracks.

But, Dylan being Dylan, has always contested that it is not autobiographical, denying that they were “confessional songs”; “a lot of people thought that album pertained to me. It didn’t pertain to me …” Yet, they are a place where he so obviously found solace in the sharing of his internal pain. But, he’d later tell Mary Travers “A lot of people tell me they enjoy that album. It’s hard for me to relate to that. I mean … people enjoying that type of pain, you know?”

Jakob Dylan later described the record as like “hearing his parents talk,” and really that’s exactly what it is, a conversation. Whether it be fact or fiction, there’s a truth and a transaction. Even as a young kid I remember sympathising with characters in the stories – naively feeling the emotions that a 30-year-old, 35 years ago felt. You are drawn into those fleeting moments where someone realises something has changed, the exact point at which your throat begins to hurt whilst your stomach drops; like the final moment you see someone before they turn a corner and they’re gone; or a mascara filled teardrop on a cheek.

Listening to someone scratch the collapse of their marriage and life in such an honest and blank canvas way, whether it is autobiographical or not, is oddly cathartic as a listener. In a communal sense, you feel his feelings, go through the anger and the bitterness, the betrayal and the affairs, and come out only wishing that the hurt parties live on happily like any relationship.

People chastise about Dylan’s imperfections, his voice, his writing, but this is an example of how imperfections matter. It’s a human record, in every damning and amazing way. It’s about mistakes, love lost, estrangement but ultimately, it’s about the bliss of how sweet life can be, along with the realisation that it can’t always give you everything.

And, like any life-defining album, it has become a soundtrack. It backs down days and up days for me, explaining moments where I’m lost and everything seems upside down; in the same way as a parent would do.

There are periods of my life I can vividly remember listening to this; going to a Sunday football match with my dad in the car, the first moment the door shut after I moved into my flat in the first year of uni, and saying a long goodbye to my girlfriend before getting onto a northbound train. And, truly great albums do that, they stick with you, your personality, the way you look at the world, everything.

Listen to Bob Dylan on Spotify and Apple Music.